München

München

In 1999, as we drove through Southern Germany on our honeymoon, we stopped for three days in München (or in English - Munich). We had been in Heidelberg for three days. On our way to München, we stopped in Nuremberg for the afternoon. Unfortunately, it rained that day. We then had to drive down the E45 Autobahn in heavy rain to München. We were there from July 23 to 26. The days we spent in München were beautiful with sunny skies. I had visited here back in 1989 with my friend Kevin, but this was Debbie's first trip here.

Munchen is in Southern Germany in the Free State of Bavaria. It sit's at an altitude of 1,669 ft. above sea level.

Although München is a bustling international city, many Münchners (that's what they're called) affectionately regard it as the largest village in Germany. These "Münchners" do not look like what you typically might think. One gets the image of men in leather pants (called Lederhosen) and feathered hats (called a Trachen Hut) drinking large steins of beer, singing beer-drinking songs while holding generously proportioned blond Fräuleins. Though you might still see these types in your local beerhall, they are the exception, not the rule.

München is the capital of the Free State of Bavaria (Seal of Bavaria at right). München is also the best loved of all German cities and sees more than three million visitors a year (I am also told that it is very expensive to live here). It's a popular city because of the relaxed atmosphere. Many inhabitants enjoy sitting in the cities numerous beer gardens enjoying their favorite beverage (which you can probably guess). Of course, Oktoberfest draws thousands of visitors from around the world every fall. As you can imagine, it's a beer lover's paradise. Somehow, Beer-hating Debbie survived her stay here. However, there is more to München than just beer. We spent three days here enjoying the cultural and historical sights. Of course, I did manage to have a few beers myself.

München has a history in the movie industry. In 1919, they had over 40 cinemas in München. A number of movies have been filmed here. Among them, The Great Escape was filmed in a pine forest outside of München while Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory was filmed almost entirely in München. Das Boot and The Neverending Story were filmed in the Bavaria Studios in München (nicknamed "Hollywood on the Isar"). You can take a 90-minute tour of the studios, though we didn't. They have a realistic reconstruction of the U-boat from Das Boot which you can go in.

This is the city flag of München. It is similar to the Bayern (Bavaria) state flag except it uses the colors of black and gold.

Debbie and I stayed in the Hotel Torbräu in the Old Town (Altstadt) section of the city. Built in 1490, the Torbräu (at right) is considered to be the oldest hotel in Munich. It's at Tal 41 near the "Isartor" and only two blocks from the center of München. The rooms were modern and comfortable. We had breakfast every morning on the balcony with the flags. When we were there, they didn't have air-conditioning, but have since added them. Debbie wasn't very happy with the guy at the front desk. She wanted to check in while I parked the car. The man would not allow this saying, "only the husband can check in." I can't write here what Debbie thinks of this policy (I would lose my PG Rating).

Walls once surrounded München, being an old medieval city. There were five fortified gates to enter the city. As the city expanded, the walls were mostly torn down in the 19th century. Three of these fortified gates are all that remains of these walls. One of three, the Isartor (Isar Gate) can be found at the end of what is called the 'Tal' (valley). The street, in which our hotel is on, Im Tal, is called as such because in the past the road from the Alte Rathaus, next to the Marienplatz, towards the Isartor went downhill. The gate tower was built in 1337 and was the main thoroughfare towards the Isar, the main river flowing through München. The facade of the Isartor is ornamented with a painting depicting the battle fought by Ludwig the Bavarian (future Emperor Ludwig I) in 1322 at Ampfing.

Celtic tribes originally settled in the foothills of the Alps. In 15 B.C. they are conquered by the Romans who incorporate the region into their province of Raetia. They later abandon the area and the people left behind form the clan of the Baiovarii.

München (or Munich in English) started out as a 9th century town built on the banks of the Isar River near a Benedictine abbey. The monks, or in German "Mönch", gave it's name to the town. In Old High German, it is "Muniche." So the town has taken as it's emblem a little monk or "Münchner Kindl" (shown at left).

In 1156, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire (1125- 90) gave a part of Bavaria to Heinrich der Löwe (Henry the Lion), the Duke of Saxony (1129-95.) To make money, Duke Henry had trade routes moved to München and thus started the town to becoming an important city. On June 14, 1158, the emperor officially granted the settlement of München the right to hold a market, thus making it a true city.

In 1180, the Duke was kicked out of Bavaria (he had run afoul of the emperor) and was replaced by the Palatine Count Otto von Wittelsbach. This started the rise of the Wittelsbach dynasty, which would rule Bavaria until 1918. In 1225, the dukes moved their government to München and made it their main residence. In 1314, one of the dukes, Ludwig der Bayer (the Bavarian) became King of Germany and then (1328) the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. At this time, München rivaled Augsburg and Nuremberg as trade centers. During the rule of Albrecht IV "the Wise", the city enjoys a high point of Gothic culture. Their idea was to make München the second Paris, including museums, libraries, universities and parks.

In 1623, Duke Maximilian I, during the Thirty Years' War, made München the bastion of Catholicism. During the war, in 1632, München is occupied by Protestant Swedish troops commanded by Gustavus Adolplhus. Two years later, the plague would kill 7,000 residents (a third of its population). In 1705, during the War of Spanish Succession, the city is occupied by Austrian troops who remain until 1714. During that time, the Austrians brutally put down a peasant uprising. During the French Revolution in 1800, French troops occupy München.

Bavaria and München would reach its height during the enlightened rulers of the 19th century. Max Joseph (1799-1825) helped to defeat Napoleon and became King Maximilian I of Bavaria. In 1810, the city started the tradition of Oktoberfest. München continued to grow as the capital of Bavaria. Maximilian's son, King Ludwig I (1825-1848) created many beautiful buildings in an attempt to make München the most beautiful capital in Europe. It becomes known as "Athens on the Isar" as the population of the city reaches 100,000. A scandal forced Ludwig to abdicate in favor of his son, Maximilian II (1848-1864) who continued the many building projects of his father.

After his death in 1864, his son became King Ludwig II, the most popular figure in Bavaria then and today. Ludwig II (at right), or as he later became known as, "Mad King Ludwig", undertook to build a number of castles around Bavaria, the most famous being Neuschwanstein. Ludwig II made the disastrous political mistake of making an alliance with Austria against the Prussians. After this, he went into a self-ordained exile in his castles in southern Bavaria. The state of Bavaria became absorbed into the new German Empire under Prussia's Wilhelm I. Ludwig II was arrested in 1886 and mysteriously drowned three days later. His son became Ludwig III and ruled Bavaria until his forced abdication at the end of World War I.

In 1918, at the end of World War I, the November Revolution begins the Free State of Bavaria. After this, the city was the scene of considerable political unrest. In 1919, Kurt Eisner, the social democratic Bavarian president wasassassinated. National Socialism (Nazism) was founded there, and on November 8, 1923, Adolf Hitler (at left) failed in his attempted München “beer-hall putsch” which was a coup aimed at overthrowing the Bavarian government. Despite this fiasco, Hitler made München the headquarters of the Nazi party, which in 1933 took control of the German national government. Michael Cardinal Faulhaber, the archbishop of München, was one of the few outspoken critics of the National Socialist regime.

The first Concentration Camp, Dachau, was opened just north of München. On the night of November 9, 1938 called Kristallnacht saw the destruction of numerous synagogues throughout Germany. This would be the beginning of Hitler's persecution of the Jews. Only 200 of München's 10,000 Jewish inhabitants survived the horrors of the Final Solution. In September of 1938, the Munich Pact was signed in the city by the major European powers who bow to Hitler’s demand to absorb the Sudeten Lands into the Third Reich, thereby hoping to appease Hitler and stop the threat of war. In 1943, during the war, a small resistance group of college students, called the "White Rose" secretly advocates the end of National Socialism. They are discovered and the Gestapo executes many of their young leaders. Because it was the headquarters of the Nazi Party, the city received special attention by the Allied air forces. München was badly damaged, over 50% of the buildings were destroyed and 250,000 citizens were killed, by71 aerial bombardments during World War II, but after 1945 it was extensively rebuilt and many modern buildings, like the BMW (Bayerische Motorer-Werke or Bavarian Motor Works) headquarters, were constructed. In 1957, the city's population reached one million people.

In 1972, München was chosen for the XXth Olympiad Games. What was supposed to be a triumphal sign of the rebirth of the city turned tragic as a Palestinian terrorist organization known as "Black September" seized a number of Israeli athletes, killing two. During an unsuccessful attempt to rescue the other hostages by the German police, nine more Israeli athletes were killed by the terrorists along with a German police officer.

However, two years later in 1974, Germany hosted the World Cup. Germany's national football team, nicknamed Die Nationalelf (The National Eleven), won the World Cup, their second World Cup title, after beating the Netherlands 2-1 (goals by Paul Breitner and Gerd Müller) in the final at Olympiastadion in München.

In 1978, Franz Josef Strauss becomes Bavaria Minister-President and develops München into a high-tech city. Today, München is the third largest city in Germany, behind Berlin and Hamburg, with a population of around 1,250,000. It is a major tourist center, especially during Oktoberfest when it attracts thousands of visitors.

Marienplatz

After settling in to our room, we set out to explore München. We headed up the Tal to the Marienplatz, which is the center of München (photo at top of the website). This square, previously called Schrannenplatz, has been the heart of the city since Henry the Lion founded München in 1158. It was a salt and corn market, tournament arena and a place of execution. A fish market was held near the Fischbrunnen (fish fountain) which is on the east side of the square. In the middle of the square is the Mariensäule (Mary's column), a marble column erected by the Prince-Elector Maximilian I in 1638 after Munich and Landshut were saved from pillaging by the Swedish army during the Thirty Years' War. At the top of the column is a gold statue to the Virgin Mary (at left), the city's patron. On the pedestal of the statue, there are four winged children that represent innocent hostages of plague, war, famine and heresy. The Mariensäule is considered the center of the city and is therefore not just a favorite meeting place - all distances in München are measured from here. They were doing restoration on the statue while we were there. So, in the photo at the top of the website, it is enclosed in scaffolding and white canvas. Luckily, on the last day before we left München, they unwrapped it and I was able to get this picture.

Bordering the north-side of the square is the neo-Gothic Neues Rathaus (new city hall). This building is incredible (photo at top of website). Built in the 1860's, the München City Hall’s neo-gothic architecture is the result of a show of strength between a local, rather conservative, politician and the München City Council. The politician opposed the Council’s plan for a Renaissance-style building to replace the old City Hall (Altes Rathaus). Eventually, München’s City Council caved in and asked Georg von Hauberrisser, then a 24-year old architectural student, to design a new City Hall. He designed everything himself, including the City Hall’s intricate façade, the labyrinth pattern on the floor of the main inner courtyard, the furniture and even the lighting fixtures.

They started construction in 1867 and didn't finished until 1908, 41 years later. The problem was, in 1874, when the new building was ready to be opened, everyone realized there was one major problem: it was too small! So, they had to tear down more buildings to enlarge it. In the end, the tore down 24 historic buildings to complete the entire project. It was during the second phase of design and construction that the City Hall’s famous clock with its Glockenspiel was added. The facade of the building is phenomenal. Though it is very noticeablewhere the first construction phase ended and the second began. Red bricks of the earlier half (right side) meet with pale stone used in the building of the extension (left side). In an effort to give the City Hall a more unified appearance, statues of the Wittelsbach royal family were added. The picture above right is of the tower on the left side (the newer part) of the building. Along with the Wittelsbach statues are many other statues of Bavaria's history and legends. There are images of local saints and many allegorical figures. There is even a bronze statue of a dragon on the side of the building. At the top of the center tower, there is a bronze statue of the Münchner kindl (small monk), the symbol of München. The clock in the tower is the fourth-largest chiming clock in Europe. Fortunately, during World War II, the building suffered little damage. The magnificent stained glass windows, twisting staircases, vaulted ceilings and the elaborately caved woodwork are, for the most part, in their original state.

When I visited München back in 1989, I climbed to the top of the 260 ft. main tower. You can also take an elevator. However, I recommend climbing to the top of the nearby Peterskirche. This way you can get a good view of both the Marienplatz and the Neues Rathaus. I did both in 1989 (I had better knees back then).

In the left-center of the front facade, about halfway up the main tower, is the Glockenspiel (carillon with 43 bells - glocken means bells and spiel means play) which you can see behind us in the photo above left. There is a musical show with brightly colored mechanical figures that moveand spin on two levels (those are the balconies with the flowers above us). They depict two episodes from München's history. The first is Schläfflertanz (dance of the coopers - barrel makers) which commemorates the end of the plague in 1517. Since they need barrels to store the beer, barrel makers are very important in München. The other show depicts a medieval jousting tournament that was held in the Marienplatz in 1558 along with the marriage of Duke Wilhelm V to Renata von Lothringen. The show goes off three times a day (11am, 12pm and 5pm - there is no 5pm show in the winter). At night, the figure of a night-watchman comes out to blow on his horn and then the Angel of Peace comes out to bless the Münchner Kindl. The interior of the building is just as magnificent as the facade. The stained glass window depicting the "Patrona Bavariae" (Mary as patron of Munich), the Law Library and the "Kleine Sitzungßaal" (small council chamber) are well worth visiting. There are six inner courtyards. You can take an elevator to the top of the tower (which I did in 1989) which is 278 ft. high and get some great views of the city.

Here I am (above right) sitting by the Fischbrunnen (fish fountain) in the Marienplatz in front of the Neues Rathaus. This fountain, which I talk more about below, was destroyed during an Allied bombing raid and rebuilt after the war. You can barely make out the fish statue on top of it.

At the eastern end of the Marienplatz (the side we entered from) is the Altes Rathaus or old city hall (seen at left) built in 1474 by Jörg von Halsbach (his nickname was "Ganghofer", and he was also the Master Builder of the Cathedral "Frauenkirche"). replacing the original one built in 1310. It has gone through several style changes- first to Baroque and then back to Gothicin the 1860's. This building has stepped gables and bell turrets. Most of the Altes Rathaus was destroyed during the aerial bombings of World War II, only the exterior walls remained intact. It has since been rebuilt to it's original look.

Next to the Altes Rathaus is the 180 ft. tall Talbruck gate tower (photo at right and left) that was built from one of the old city gates. This was once the eastern boundary of the city when the original 1175 wall went around it. The city expanded further east and a new wall was built in 1330. The Talbruck gate tower, which was leveled to the ground during World War II, wasn't rebuilt until 1975, however it was re-built based on it's appearance prior to 1474. Inside the Altes Rathaus is a toy museum. There are three arched walkways at the base of the building.

Like everywhere else in Germany, football or fußball (soccer) is the main sport. München has two local professional fußball (soccer) teams. The most famous worldwide is FC Bayern München (Munich Bavaria Football Club), who wear red shirts and white shorts and play in the 69,901 seat Allianz Arena. With 2 Intercontinental Cups, 4 European Champions League titles, 1 UEFA Cup title, 1 Cup Winners' Cup title, 20 national championships and 13 German Cups, FC Bayern München is Germany's foremost football club. Bayern München, also known by their nickname, Die Bayern (the Bavarians) was founded in 1900 by members of a München gymnastics club. Their first national honor was in 1932 when they won the German championship by defeating Eintracht Frankfurt 2-0 in the final. The advent of the Hitler regime put an abrupt end to Bayern München's development. The president and the coach, both of whom were Jewish, left the country. Many others in the club also saw themselves purged. In the following years, Bayern München, taunted as the "Jew's club", decayed into irrelevance.

After the war, Bayern München slowly climbed back into prominence. In 1965, the joined the Bundesliga (Germany's top league). That year, with future superstar Franz Beckenbauer, the won the German Cup and then the UEFA European Cup Winners' Cup (a secondary championship between the winners of the European domestic cup competitions - not as prestigious as the UEFA Champions League European Cup, which is an annual football competition among the most successful football clubs in Europe). From 1973 to 1975, Bayern München won three consecutive UEFA Champions League European Cups. In the 1980's and 90's, Bayern München had some up and down seasons. However, they turned it around in 1998 when they hired Ottmar Hitzfeld, who became the most successful Bayern coach of all time. In 2001, the won their fourth UEFA Champions League European Cup. They continue to be one of the more dominant football clubs in Europe winning seven German national championships in the last 10 years.

From 1972 to 2005, Bayern München played in the Olympiastadion (site of the 1976 Olympics). The stadium was host to three UEFA Champions League European Cups and the 1974 World Cup finals (which resulted in a 2-1 victory for Germany over Holland).

Bayern München traditional rival is TSV 1860 München who currently play in the second level of the Bundesliga. It officially started as a sports organization back in 1860. It's nickname is Die Löwen (The Lions). In 1942, during World War II, they won their first German Cup. In 1963, the became one of the first members in Germany's new national league, the Bundesliga (Bayern München would not be allowed to join for another three years). The continued to do well in the 1960's, winning their second (and last) German Cup in 1964. In 1966, they were Bundesliga champions.

After this, TSV 1860 München started to slide downward, eventually being relegated to the second level in 1970. In the 1970's and 80's, they had been promoted to the top level twice, but immediately was relegated again. They returned in 1992 and managed to compete for a decade. However, in 2004, they were relegated again where they are today. Currently, they share Allianz Arena with Bayern München.

Germany is hosting the 2006 World Cup (Weltmeisterschaft) and München is one of the sites for games to be played. This is the second time the World Cup has come to Germany. West Germany hosted it back in 1974 with a number of games, including the championship game, played in Olympiastadion in München. In 2006, they will host four 1st Round games, including Germany's opening game 4-2 win over Costa Rica, one 2nd Round Game and a Semi-Final game. In 1974, the games were played in the Olympiastadion, the 2006 World Cup games will be played in the brand new 66,000 football stadium, the Allianz Arena, located in the northern suburb of Fröttmanning which was completed in 2005. The outside of the stadium has a smooth facade formed from translucent, lounge shaped cushions that glow in a variety of colors (its lit up in red when Bayern München play, in blue when TSV 1860 München play and in white when in use by the German National Team). The cost to build the stadium was € 286 million (Euros). Within a few months of opening day, the distinctive shape of the Allianz Arena had inspired the nickname Schlauchboot ("inflatable boat") by which it is now commonly known.

München also has a professional ice hockey team, the EHC München (Eishockeyclub München). Hockey has been played in München since 1909. They have had professional hockey teams play in München since then. Some teams, like EHC 70 München went bankrupt. In 1983, the EC Hedos München began play but it also went bankrupt in 1995. the current professional hockey team, EHC München was started in 1998 and plays it's games in the 6,256 seat Olympiaeisstadion (Olympic Ice Stadium). Professional ice hockey in Germany is not as well organized as it is in many other countries. Today, German professional hockey is divided into two levels in which EHC München plays in the second called the Eishockeyspielbetriebs gesellschaft or ESBG which has 14 teams. Recently they started a women's hockey team.

München Churches

There are many churches in München, with most of them being Roman Catholic. We walked east from the Marienplatz to the Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady), which has become the symbol of München. Duke Sigismund laid the foundation stone in 1468. This 500-year old church took 20 years to build and was completed in 1488. It will never be confused with many of the beautiful cathedrals of Europe. This Late Gothic style church is done in plain dark red bricks and has a bright red roof. The sides of the church are very plain with just old tombstones built into the walls. There are two 328 feet tall towers topped with domes, which make the church unique. The green belfries of its soberly decorated towers are in the form of the so-called ‘Welsh Hood’. They demonstrate the transition from Gothic to Renaissance. The towers have become a symbol of München partly because they survived the intense allied bombings during World War II and partly because they remind them of two overflowing beer steins. There is an elevator to the top of the south tower but you have to climb 86 stairs just to get to the elevator.

After the World War II Allied bombings, only the shell of the cathedral remained. Workmen and architects combed the rubble and salvaged every scrap that they could. The Gothic cathedral has been beautifully restored. Inside, there is a high vaulted ceiling supported by large pillars. There is a large exceptionally extravagant mausoleum for Holy Roman Emperor Ludwig I (1287-1347); a.k.a. Ludwig the Bavarian or King Ludwig IV, in the south aisle that was constructed well after he died (1622). This has to be seen to be believed. He was the first Bavarian king to be crowned emperor. Ludwig isn't actually in this monument, but is downstairs in the crypt. One of the most interesting things inside the church is the memorial grave in black marble of Prince Elector Kurfürst Maximilian I. At the far end of the choir, there is a staircase that leads down into the Bischofs-und-Fürstengruft (Bishops' and Princes' Crypt). There are tombs to various bishops of München and 46 Wittelsbach princes here including Ludwig III, the last king of Bavaria who was deposed in 1918 and died three years later.

There is also the 'footprint of the devil' or Taufelstritt. According to the legend, the architect of the Frauenkirche, Jörg von Halsbach, promised the devil you could not see a window from the inside of the church. In return, the devil would help him build the Frauenkirche. The Devil, of course, thought that meant that the church would have no windows. After he completed the building, the devil saw the church from the outside with it's many windows. He figured that he had won the soul of the architect. However, the architect led the devil to the middle of the church from where you could not see a single window, although all churchgoers would sit in areas where a lot of light came through the many stained-glass windows. The devil was so angry that he had been tricked that he stamped his foot with so much rage that his black hoofed footprint is visible in the stone floor to this day. After post World War II rebuilding, the spot is no longer hidden from windows but the footprint is still visible. In 1993, the church celebrated its 500th anniversary.

West of the Marienplatz, on the Fußgängerzone (Neuhauser Straße), is Michaelskirche (St. Michael's Church). It is wedged between other buildings, so you may not notice that it is a church at first. This is one of the more famous Renaissance churches in Germany. This Jesuit church was completed in 1597. There is an interesting answer as to why the church does not have a tower. When the first tower was destroyed while being built, Duke Wilhelm V took it as a bad omen and built a much larger church, but without a tower. There are statues to the Bavarian kings who were very good Catholics. There is a statue between the main doors of "St. Michael slaying the Dragon." It has a single nave covered by a huge cradle-vaulted ceiling supported on massive columns abutting the walls. It has second largest free-standing vault in the world.

There is a large monument in the north transept that contains the tomb of Napoleon's stepson by his marriage to Josephine and French general, Eugene de Beauharnais (his father, also a general, had fought in the American Revolution but was later guillotined during the French Revolution's Reign of Terror). He married one of the daughters of Emperor Maximilian I (Princess Augusta Amelia) and who lived in München after the downfall of Napoleon. He died in there in 1824. Below the church, there is a large crypt that contains around 30 to 40 Wittelsbach princes and kings, including Duke Wilhelm V and the most famous of the them all, "Mad" King Ludwig II. His tomb is also quite extravagant though not as much as Emperor Ludwig's in the Frauenkirche.

Further west of Michaelskirche on the Fußgängerzone (Neuhauser Straße), near the Karlstor, is the Bürgersaal. Built in 1778 as an oratory for theology students, it is a two-story church. The upper church as dazzling Rococo stucco work. During World War II, some of the interior was damaged by fire and some of the decorations had to be restored. The lower church has the tomb of Father Rupert Mayer. When the Third Reich began in 1933, Father Mayer,a Jesuit priest, openly condemned the Nazi leaders in his weekly sermons at St. Michael's church and in other gatherings. In the late 1930's he was arrested by the Nazi's and imprisoned. There was reluctance to kill him, as it was feared he would be martyred and gain even more followers in death than he had in life. By August of 1940, it was clear to the Nazis that Father Mayer's stay at the Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen concentration camp had affected his health considerably. Rather than let him die a martyr, they decided to confine him to a monastery in the Bavarian Alps. He was isolated there until he was freed in 1945 at the end of the war. Father Mayer died of a stroke soon after. Pope John Paul II beatified him in 1987.

Across the Marienplatz is Peterskirche (St. Peter's Church) which is shown at right here. The picture at left is the spire and roof of Peterskirche taken from behind the church on Sparkassen Straße next to the Viktualienmarkt. The church is also known locally as Alter Peter (Old Peter). This is the oldest church in München and is on the highest ground. Before the city of Munich was founded there was already a small chapel on the "Petersbergl" (Peter's hill) replaced at the beginning of the 11th century by the romantic style Peterskirche (Peters church). The basilica formed part of the monastery which the city received it's name. In 1294, a new gothic church was built, which was constantly rebuilt and changed in style over the years. It once had two towers, which were combined into one. There are many art treasures from various eras such as the gothic altar, the baroque baptismal font and the rococo side altars. The church was so badly damaged from bombings during World War II that the repair work lasted until 1975.

The Renaissance tower "Alter Peter" is, along with the Frauentürmen (Ladies Towers), a Munich landmark. After paying DM 2,50 you can climb 302 wooden steps to reach the viewing platform and enjoy a wonderful view over Munich (it's open from 9 to 6). You can see a bunch of people enjoying the view. I took this photo from the top of the On the way up, you can see the seven bells. The tower also has eight clocks. I made this accent during my first trip to München in 1989 but Debbie and I choose to stay at street level this time. I took this photo from the top of the Neues Rathaus.

Right nearby at the intersection of Sparkassen Straße and Im Tal is the Heilig-Geist-Kirche (Church of the Holy Spirit - Geist is German for ghost) which is shown at left here. It is open in the morning and late afternoon. This 14th Century Gothic church is one of München's oldest and most ornate. The site once had a chapel, a hospital and a pilgrims' hostel. In 1724, the church was completely redone in a florid rococo style. In 1729, the tower was added. The facade is Neo-Gothic and was re-done in 1888. It has an incredibly ornate interior, which combine Gothic and late Baroque styles. The painted vaulted-ceiling depict scenes from the hospitals history. The high altar was made in 1728. Allied bombings during World War II

destroyed the roof and most of the interior of the church. Only the outside walls and spire (without the copper dome) remained. The Heilig-Geist-Kirche was re-built after the war. Some of the original parts of the altar survived. There are some bronze figures in the entrance of the church that originally formed part of the tomb of Ferdinand of Bavaria.

On the right we have a picture of the Altes Rathaus (Old City Hall) on the left and further in the background on the right is the spire of the Heilig-Geist-Kirche.

North of the Marienplatz is the Odeonplatz. On the west side of the Odeonplatz, on Theatinerstraße, is the Theatinerkirche (photo below left). This is a basilica in the style of the high Baroque and is considered to be one of the most beautiful churches in München. The church was a gift to the people of München by Elector Ferdinand and his wife in thanks for the birth of their long-awaited heir, Max Emanuel, in 1662. When you see the church, you figure that they must have waited a long time for this kid to be born.

The church is dedicated to St. Cajetan and is run by the Theatine Order of monks (thus the name). Construction began in 1663 and took six years. It is based on Sant'Andrea della Valle in Rome (which we visited in 2003). The dome and towers were added later and then finally in 1770, the facade. There are marble statues to four saints in the niches in the facade (including one to St. Cajetan himself). I had no idea who this saint was until I did some research. He was a Venetian noble (from Venice) who lived from 1480 to 1547. He was the founder of the monastic order that runs the church. The name "Theate" is from a Latin nickname for St. Cajetan's friend and the first superior of the order, the future Pope Paul IV (Paul IV was responsible for confining Jews to ghettoes in Rome and other cities and is buried in Santa Maria sopra Minerva church in Rome where we visited in 2003). This yellow color is somewhat common throughout München.

The interior of the Theatinerkirche has barrel vaulting and high dome. It is painted white with lavish decorations done in stucco. There is an immense high altar with more salutes of saints on it. Beneath the high alter, down in the crypt is the massive stone sarcophagus of King Max and his wife Marie of Prussia (the parents of "Mad" King Ludwig II - who is buried over in St. Michael's) along with bronze coffins containing some other members of the Wittelsbach family. You have to pay a small fee to enter. Among the other coffins is Emperor Charles VII (a Bavarian elector who fought against Maria Theresia of Habsburg in the War of the Austrian Succession and lost), Prince-regent Luitpol (he deposed "Mad" King Ludwig II in 1886 and ruled as regent for Ludwig II's brother, the insane king Otto), King Otto of Greece (Max's brother and Ludwig II's uncle who became king of Greece in 1832 and was overthrown by the Greek army in 1862) and the more recent member of the Wittelsbachs, Ludwig III's son, Rupprecht (Rupert) who died in 1955.

München Palaces

There are two major palaces you can see. One, the Residenz is in the Old City and the other, Nymphenburg, is built in the suburbs, two miles east of the city center.

The Residenz (residence) was the successor of the Alte Hof as a residential site of the ruling family Wittelsbacher up until 1918. Construction began back in 1385. They kept adding to it through the centuries. There are numerous courtyards and fountains inside. Today, it is an enormous complex of buildings constructed around seven courtyards. The have a few lion statues outside the entrances (left). The Residenz was very famous for its beauty in the 17th century. King Karl Gustav of Sweden wanted to transport the whole building by Swedish troops on rollers to his home in Stockholm. In World War II, the Residenz was almost completely destroyed by aerial bombings. After hard work of restoration, it is now a museum. One section of the Palace not to be missed is the Treasury. Here you can see the Wittelsbach treasures, including the Crown Jewels and Royal Regalia. Mad King Ludwig II had his royal apartment here. Unfortunately, the rooms here are recreations. The original rooms were completely destroyed during the World War II bombings. These rooms were located in the north-west corner of the Palace, which was the part where the allied bombs fell heaviest. Ludwig II had a corridor redecorated with scenes from Wagner's 'Ring'. A few of these paintings survive, but, once again, most were destroyed in the war.

The other large palace is Schloß Nymphenburg (Nymphs' Castle). After the birth of Maximilian Emanuel, the heir to the throne, his father, Duke Ferdinand Maria, had this suburban palace built for his wife (in addition to the Theatinerkirche). The queen named it and even supervised the building (I guess she didn't trust the contractors - can you blame her?). All around the palace are landscaped gardens, ponds with swans, smaller buildings and a number of enchanting garden pavilions. It became the royal summer palace for the Wittelsbachs. There is a museum here that has among other things, royal coaches, carriages and sleighs. Ludwig II's coronation coach is also here. Ludwig II was born here in the palace back in the early hours of August 25, 1845. The room in which he was born has been restored to its appearance in that year. We didn't tour the palace. I guess we were palaced out.

Luitpold, the cousin of Carolingian king Arnulf, who died in 907, founded the Wittelsbach family (royal crest at left). He was the ancestor of Otto II, Count of Dachau who purchased the castle of Wittelsbach, which once stood on the Paar River in Bavaria (it was destroyed in 1208). They took their name from the castle.

In 1180, after Emperor Frederick Barbarossa kicked out Heinrich der Löwe (Henry the Lion) he replaced him with Count Otto von Wittelsbach. This started the Wittelsbach dynasty which would rule Bavaria until 1918.

Otto died three years later and was followed by his son, Ludwig I (Ludwig is German for Louis) who moved the government to München and made it also the main residence of the Wittelsbachs. Unfortunately for Ludwig, an unknown assassin stabbed him to death in 1231. After the death of Ludwig's son, Duke Otto II in 1253, Bavaria was divided among Otto II's two sons.

After the Duke of Lower Bavaria died childless in 1340, Duke Ludwig III of Upper Bavaria united the two Bavaria's. Ludwig III or "Ludwig der Bayer" (the Bavarian) became King of Germany and then in 1328 he became Ludwig IV the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (He was the 3rd Duke but the 4th emperor to be called Ludwig - confused yet? - however, he was the first Wittelsbach to become an emperor).

The Holy Roman Empire (in German - Heiliges Römisches Reich) was a political conglomeration of lands in western and central Europe during the Middle Ages. At the time, you had to be elected king before you could be elected emperor. German kings were always elected. In the time of Charlemagne, they were chosen by the leaders of the Germanic tribes (there were five of them). Later, certain dukes would elect the kings and emperors. In 1356, this was made official with seven specific people called "Electors" (how creative), four were rulers and three were archbishops. Otto the Great became the first Holy Roman Emperor in 962. His successor was his son (who was also elected) and this practice continued until 1024 when Emperor Heinrich II (St. Henry) died childless. After this, sons were not elected and the complicated system of elections started.

While he was still a duke, Ludwig was having trouble with Pope John XXII, who had excommunicated Ludwig in 1324. Ludwig went to Rome in 1328 to have himself crowned emperor (it was a tradition) and while he was there had a new pope elected, Nicholas V (later referred to as an Antipope). Nicholas was forced to abdicate two years later.

After the death of Ludwig's grandson Stephen in 1375, Bavaria was divided again, this time among Stephen's three sons; one ruled Ingolstadt, one ruled Landshut and one ruled München (all are cities). This lasted for 128 years.

Duke Albrecht IV "the Wise" united the three parts in 1503 (Albrecht is German for Albert). He ended the influence of the Italian Renaissance. Albrecht's decedents continued to rule Bavaria. Albrecht V (1550-79) built a library and created the first art collection in Germany. In 1597, his son, Duke Wilhelm V (Wilhelm is William in German) brought Bavaria to bankruptcy and then abdicated in favor of his son Maximilian. Duke Maximilian I "the Great", a Catholic, made München the bastion of Catholicism. He started to persecute Protestants which led to the Thirty Years' War in 1618 which devastated Germany. The following year, Maximilian was asked to become emperor, but he declined. However, in 1623, Maximilian would become an "Elector." Maximilian ruled Bavaria throughout the war, even when Swedish troops occupied München in 1632. His son, Ferdinand Maria, succeeded him upon his death in 1651.

Ferdinand Maria's son, Maximilian II Emanuel, became duke and Elector in 1679 at the age of 17. Two years later, the plague would devastate Bavaria (killing a third of its population). In 1705, during the War of Spanish Succession, the city was occupied by Austrian troops who remain until 1714. During that time, the Austrians brutally put down a peasant uprising. During the French Revolution in 1800, French troops occupy München.

In 1742, Elector Karl Albrecht (Charles Albert) of Bavaria was chosen as Holy Roman emperor and became Karl VII. Shortly after his election, Bavaria, which was involved in the War of Austrian Succession, was again overrun by Austrian troops. His son, Maximilian III Joseph was more of a composer and did not have any political ambitions. With his death in 1777, the Bavarian branch of the Wittelsbachs died out, and the Palatinate-Sulzbach line acceded in Bavaria in the person of the not very popular Duke Karl Theodor, who did little for Bavaria, and who died in 1799 without a son. Duke Maximilian I Joseph, who was duke palatine of Zweibrücken, senior member of the Palatinate branch, at a very young age, succeeded him. He united all Wittelsbach lands under his sole rule and who in 1806 became the first king of Bavaria.

Bavaria and München would reach its height during the enlightened kings of the 19th century. Max Joseph (1799-1825) helped to defeat Napoleon and as his reward, Bavaria went from being a duchy (ruled by a duke) to a kingdom (ruled by - you guessed it - a king). Max Joseph became King Maximilian I of Bavaria (Bavaria's first king). Maximilian's son, King Ludwig I (portrait at right - he does dress the part) became king in 1825 at the death of his father. Ludwig was a lover of arts, antiques and women. In 1848, a scandal forced Ludwig I to abdicate in favor of his son, Maximilian II. What was the scandal? Ludwig took Lola Montes, an Irish-born singer and dancer, as his mistress. The shocked Bavarians revolted and Ludwig I saw he had to step down (Lola fled to the United States where she continued her career, dying in New York City at the age of 40).

Maximilian II was a good ruler, but not a healthy one. He died at the age of 52. After his death in 1864, his son became King Ludwig II, the most popular figure in Bavaria then and today. Ludwig II, or as he later became known as, "Mad King Ludwig", undertook to build a number of castles around Bavaria, the most famous being Neuschwanstein and Linderhof (I have pictures of these two castles in my Oberammergau page). Ludwig II made the disastrous political mistake of making an alliance with Austria against the Prussians. After this, he went into a self-ordained exile in his castles in southern Bavaria. The state of Bavaria became bankrupt because of Ludwig's castle building. Ludwig II was declared insane by the government when he said he wanted to build more castles and arrested in 1886. He mysteriously drowned three days later in a lake near one of his castles (he drowned in three feet of water and he was a good swimmer - hmmmmm).

Ludwig II's younger brother Otto was also insane and was soon replaced. Ludwig and Otto's uncle Luitpold (he was the son of Ludwig I and Maximilian's younger brother) became regent (he wasn't actually king but ruled like one). He was popular and anti-Prussian (which is probably why he was so popular). After his death in 1912, his son became Ludwig III and ruled Bavaria until his forced abdication toward the end of World War I. He was pro-Prussian and not so popular. As post-war revolution swept Bavaria in 1919, Ludwig III and his wife fled to Hungary, where he died in 1921. After 783 years in power, the rule of the Wittelsbach family in Bavaria was at an end.

The Wittelsbach, though not in power, continue to live in Bavaria today. They claim to never have given up their right to rule Bavaria. In 1996, after the death of his father Albrecht (Albert), Duke Franz (Francis), who is the great-grandson of Ludwig III, took over as the head of the Wittelsbach royal family and heir to the throne of Bavaria. Franz was born in 1933 and was at the age of 11, along with his family, imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps during the last year of World War II. The U.S. Army freed him from Dachau in 1945.

Strangely enough, Duke Franz (photo at left) is also considered by the Catholic Jacobites as King Francis II of Great Britain. He is descended from King Charles II, whose younger brother King James II of England (who New York is named after) was kicked off the throne in 1688 for being Catholic (the English didn't like Catholics back then - in fact, the law today says that you can't be King and Catholic - though some are trying to change it). The Catholic Jacobites have been trying to get the throne back ever since 1688. Of course, it's not likely that Queen Elizabeth II is going to give up the throne for Franz but the Jacobites still can hope.

In the year 1175, the first city wall of München had been built. It had an outline in the shape of a spade. The original city went from the Augustiner Straße next to the Frauenkirche to Peterskirche and the Sparkassen Straße. The Altes Rathaus, next to the Marienplatz, was built over one of the original city gates. It was only about three-fourths of a mile wide. If you are wondering what the symbol "ß" is. It is called an "Eszett" and is pronounced like a double "s". In addition, the word Straße or Strasse is, if you haven't already guessed, the German word for street.

The München "spade" rapidly grew and about 1330, a second city wall was built further outside the first. Its horseshoe-shaped form characterizes the outline of the center of the München today. From the old town gates the 'Neuhauser Tor' (built about 1300, nowadays called 'Karlstor'), the 'Sendlinger Tor' (built about 1310) and the 'Isartor' (built about end of the 13. century) are still preserved. This picture above is of the Karlstor (Charles' Gate) and was taken from the Fußgängerzone (Neuhauser Straße) lookingthrough to the Karlsplatz which the locals call "Stachus" (the name of a popular inn that stood here since 1759). They have a large water fountain here (more on that below). The gate was severely damaged during World War II and had to be rebuilt afterwards.

Neuhauser Straße stretches from the Karlsplatz to the Marienplatz and is closed to traffic. It is a large pedestrian walk called a Fußgängerzone (in German this translates to 'foot going zone'). It's full of restaurants and stores. It's always full of people. One of the things you see throughout Europe and especially in München are the outside musicians playing for a few coins. Mostly violin players doing Mozart, but not all. We went in a store front where an opera singer was doing the "Marriage of Figure". The acoustics in there were fantastic which is probably why he uses it. Of course, there was one girl who, we think, was practicing her saxophone lessons outside and hoping to get a few coins for it. As far as this guy here on the right, who knows? He does look interesting though in his traditional Bavarian dress, lederhosen in all.

Fountains and Statues in MünchenGermans have a fascination with water fountains. Every city and town we visited had more then a few. Which is fine by me since I love them too. Here are some of the ones from München. If those khaki-clad tourists below backed up anymore they would be quite wet.

This is the large fountain in the Karlsplatz. People sit around the fountain on the rocks and have their lunch. The 199 nozzles create a comfortable atmosphere. This large square was created in 1791 when they tore down the old city walls (though the fountain was created in 1972). This was the edge of Medieval München. Behind us was once just farmlands outside the city gates. The large building behind us on the right is the Justizpalast (Palace of Justice). In front of us is the Karlstor and the entrance to the Old City.

Brunnenbüberl Richard Srauß Brunnen Fischbrunnen

Here are some more fountains. The one on the left is the Brunnenbüberl or "Fountain Boy." The statue is on the Neuhauser Straße just inside the Karlstor. It's a statue of a young boy having water spitted on him by an older looking gentleman. I like this statue because of the humor involved. The expression on the guys' face as he spits the water is great. In addition, the guy, which only has a head is done in granite while the small boy is in bronze. A little further down Neuhauser Straße, in front of Michaelskirche is the Richard-Strauß-Brunnen. This fountain as bas-reliefs on the central column illustrating scenes from the opera "Salome" which was written by München composer Richard Strauss in 1905. I like the palm trees around the fountain. This picture was tough to take. Some elderly women, for whatever reason, was determined not to let me photograph the fountain. On the right is an older looking statue, the Fischbrunnen or "Fish Fountain" (this is the one I am photographed with in an above photo). It's in the Marienplatz outside the Neues Rathaus and was built in 1865 (and rebuilt after 1945). This is a favorite hangout for the young people of München (don't ask me why). On top of the fountain (which you can't see in the picture) is a large fish. I like the way they have the water pouring out of the girl's bucket as she examines the fish. You probably guessed that "brunnen" is the German word for fountain.

There are many statues around München. This statue at left is of Maximilian I Joseph (Bavaria's first king), in the appropriately named Max-Joseph-Platz, in front of the Nationaltheater (in photo behind the statue). The statue was erected ten years after his death. He didn't want it put up. He didn't think the pose made him look sufficiently majestic. Here is a statue of a man dressed in a toga holding a scepter on a throne supported by lions, but he didn't think it made him look like a great king. Go figure.

Max-Joseph-Platz was created in the 19th century next to the Residenz (the official palace of the Wittelsbachs) and in front of the Nationaltheater. Built in 1818, The National Theater was modeled after Greek temples and also doubles as theNational Opera House. A number of Richard Wagner's operas were first performed here. The Nationaltheater was destroyed during World War II bombings and was completely re-built in its original form and re-opened in 1963.

At right is a statue of King Ludwig the Bavarian on his bronze horse. The statue is on a pedestal flanked by statues of art, religion, poetry and industry. Ludwig was the son of Max Joseph (his portrait is above in the "The Wittelsbach Dynasty" section. The statue was erected in 1862, it is in Odeonplatz at the beginning of Ludwigstraße.

There was once was a Medieval city gate here, the Schwabinger Tor, that was demolished in the early 19th century. Max Joseph, along with his son Ludwig, wanted to organize this area of München north of the Residenz and Theatinerkirche. Therefore, they had the large Odeonplatz built as the "Street of the Sciences". This large square takes its name from the Odeon, an old concert hall built in 1828 and destroyed in 1944. The square was the destination of Hitler and the Nazi's during the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923 (they were stopped just short of the square).

Englischer Garten

One afternoon, we walked over to the English Garden or Englischer Garten. It's a large city park in the University section of the city, München's version of Central Park. It has that name because it is laid out like an English landscaped garden (a 900 square acre one). It is one of Europe's largest city parks. It was originally designed for military use, but in 1789, it quickly became a municipal park in the hope that the French Revolution would thereby be kept from inflaming Bavaria also. Thus originated Europe’s first public park, which meanwhile has grown into an area covering 1.4 square miles, the largest uninterrupted parkland of any major German city. There are a great many scenic streams along with large grassy areas. A popular attraction is the Japanese Tea House, a pavilion donated to the city on the occasion of the 1972 Olympic Games. Ever since, a tea ceremony is held every other weekend. Debbie and I walked past the Japanese waterfall along the Eisbachto to the Monopteros. It's a Neo-Classical Greek temple style building that has great panoramic views of the city (above photo). In the photo, you can see the dome of the old Army Museum, now part of the Bavarian State Chancellery, at left. Next to it is the spire of Peterskirche alongside the tower of the Neu Rathaus. Next are the two largest spires of the Frauenkirche with the dome and tower of the Theatinerkirche at right. From here it’s only a short walk to the Chinese Tower, München’s most celebrated monument in song and poetry. The pagoda was built in 1789 after the one at London’s Kew Gardens. From here you can visit to the beer garden or the Kleinhesseloer Lake.

There are other parks throughout München, though none are even close to being this big. Debbie and I walked through the Hofgarten near the Residenz. The Hofgarten exists since the 17th century and was only used by the members of the court. Since 1780, it has been open for public and it became a frequented place for locals to have their Sunday afternoon walk. They also have a good floral display.

Further outside München's center is the Olympiapark (Olympic park). This was the site of the 1972 Summer Olympics. It is a major attraction of München. Debbie and I didn't go here, but I visited the park back in 1989. It is not only the sport sites for soccer (Olympic stadium) and swimming, which attract millions of visitors every year, the whole architecture and gardening is worth it. Olympic Stadium is covered with a tent-like roof. There is an artificial lake in the middle surrounded by the Olympic tower and a hill. The hill was made from the debris of destroyed buildings after World War II. You can go up in the tower, which I did in 1989. At 951 feet high, it is Germany's highest television tower. It has a revolving restaurant at the top, and offers spectacular views.

München Cemeteries

We actually didn't visit any cemeteries in München, though there are quite a few. There are none in the center of the city. If you want to see one, you must travel outside the city center. Of course, if you are famous enough or royalty, you can be buried in one of the many München churches, but for the rest, you must go to the cemeteries. Cemeteries are called Friedhofs and usually have the clever names of Nordfriedhof (northern cemetery), Westfriedhof (western cemetery) or Ostfriedhof (eastern cemetery).

The Alte Suedfriedhof (old southern cemetery) contains almost all VIPs of München from the 19th century. Since 1789, it was a main cemetery for all of München. Among the famous people here are painters, poets, scientists and inventors. Waldfriedhof Cemetery (Woodland Cemetery) has more recent famous people like German admiral Alfred von Tirpitz and Nazi film producer Leni Riefenstahl (she has a very interesting gravesite). The one here more known to Americans, and especially James Bond fans, is Karl-Gerhart Fröbe or as he is known to Agent 007, "Goldfinger" ( Fröbe has a more idyllic gravesite).

München Museums

We visited a number of museums while in München. We spent one morning in the Deutsches Museum. Founded at the turn of the 20th century, the Deutsches Museum has become the world's largest science and technology museum with over 10 miles of exhibits (17,000 items are on display of the 80,000 that they have). Hands-on activities and fascinating demonstrations of human accomplishment, from classical mechanics to telecommunications, from a full-size reconstructed coal mine to space travel technology.

The museum was built in the late 1920's on an island in the Isar River. Inspired by London’s Science Museum, it was founded in 1925 by Oskar von Miller and today boasts 1.3 million visitors annually. It has a planetarium also. We couldn't see the whole museum (no one could in one day) so we walked around some of the main exhibits. The largest section of the museum was the Transportation section. It is dedicated to land, water and air transport as well as space flight. In the Motor Vehicles and Motorcycles section they have some old bicycles and motor cycles. They have about 40 historical passenger cars. They have the first car made by Carl Benz in 1886. They have cars made by Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Opel, Volkswagen, Daimler and the elegant 1939 Horch 853 A Sport-Cabriolet. This was a very popular town car in its time.

They have a large collection of railway locomotives and cars. They have 18 original locomotives, among them the first steam engine, built in 1814, called "Puffing Billy", the first electric engine built in 1879 along with the legendary 1912 Bavarian express steam locomotive (painted bright green). They also have a model railroad set-up, but not quite as large as the one in the museum in Luzern, Switzerland.

My favorite section was the Aerospace exhibit. The aircraft hall is two stories high and has a large collection of 50 airplanes on the floor and suspended from the ceiling. They have World War I aircraft like the Fokker Dr.I Dreidecker painted red like Rittmeister Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen's, also known as "the Red Baron", plane (above) and World War II aircraft like the Messerschmitt Bf 109 E (at right). The Messerschmitt, or ME-109, was the workhorse of the German airforce, or Luftwaffe, during World War II. Over 35,000 of these planes were built. On the main floor is a Messerschmitt Me 262. This was the first mass produced jet fighter. It was produced by the Nazi's, however, they were made so late in the war as not to be a deciding factor in the air war over Germany.

Manfred von Richthofen was the top ace of World War I. The German's called him "der rote Kampfflieger" (The Red Battle-Flyer). The French called him "le petit rouge" and he is known in the English speaking world as the "Red Baron". He is credited with 80 victories before being shot down and killed on April 21, 1918 at the age of 25. The red painted Fokker Dr.I (as seen above) is mostly associated with Richthofen, however, he only flew it at the end of his career and shot down only two planes while flying it. After his death, Richthofen's brother Lothar carried on his tradition shooting down 40 planes before he was forced to retire. Richthofen's eventual successor was Hermann Göring (who would later become the head of the German Luftwaffe and a particularly infamous Nazi), who chose to paint his aircraft completely white, ending the reign of the blood-red German fighters. The red tri-plane here in the museum is not Richthofen's plane. After being shot down, the plane was ravished by souvenir hunters.

Another similar museum is the BMW Museum, which is outside the city next to the Olympic Park. We didn't get a chance to visit here, after the Deutsches Museum it seemed like overkill. The museum was opened in 1973 and chronicles the development of BMW cars and other vehicles. The futuristic architecture is interesting also. The museum is shaped like a large teacup (I have no idea why). When I was at the top of the Olympic Tower in 1989, I was able to see the large BMW logo on the roof. Next to the museum is the BMW headquarters. These buildings can be seen in the original "Rollerball" movie with James Caan.

We visited the Alte Pinakothek (Old Picture Gallery) on one afternoon. This world-famous museum opened in 1836. The Alte Pinakothek contains some of the world's finest collections of European paintings. It is in the Kunstareal (Art District). The Kunstareal consists of the three "Pinakotheken" galleries (Alte Pinakothek, Neue Pinakothek and Pinakothek der Moderne), the Glyptothek, the Staatliche Antikensammlung (both museums are specialized in Greek and Roman art), the Lenbachhaus, the future Museum Brandhorst (a private collection of modern art) and several galleries.

The Alte Pinakothek collection was begun by William IV (1508-1550) who ordered important contemporary painters to create several history paintings. Elector Maximilian I (1597-1651) acquired paintings, especially of Albrecht Dürer. Maximilian's grandson Maximilian II Emanuel (1679-1726) purchased a lot of Dutch and Flemish paintings when he was Governor of the Spanish Netherlands. Also, his cousin Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine (1690-1716) collected Netherlandish paintings. After the reunion of Bavaria and the Palatinate in 1777, the galleries of Mannheim, Düsseldorf and Zweibrücken were moved to Munich, in part to protect the collections during the wars which followed the French revolution.

In 1836, this collection was opened to the public. There are 800 works of art by German, Dutch, Flemish, French, Italian and Spanish artists. Some of the more famous artists represented here are Albrecht Dürer Self Portrait (at right), Frans Hals, Peter Paul Rubens The Abduction of the Daughters of Leucippus (The Rubens Collection is the largest one worldwide), Hans Holbein, Rembrandt van Rijn The Holy Family, Murillo Baggar Boys Eating Grapes and Melon and a Madonna and Child by Leonardo da Vinci. The museum's collection also include the Canigani Holy Family, which was the first painting by Raphael to be brought to Germany.

During World War II, the museum was closed. The paintings were stored at first in München and then, in 1942, moved out of the city, which helped keep losses at a minimum. A number of Allied bombing raids severely damaged the building. The museum was completely rebuilt after the war, re-opening in 1957 (unfortunately the ornate, pre-war interior was not been restored).

Located across the street from the Renaissance style Alte Pinakothek, is the Neue Pinakothek (New Picture Gallery) shown at left. It's a modern concrete, glass and granite building featuring art from the late 18th to the 20th century. The Neue Pinakothek offers an overview of European art from classicism to art nouveau. Its founder was King Ludwig I of Bavaria, who opened the museum in 1853 and had it built to house his privately financed collection of works by contemporary artists. Its displays include works of the French and German Impressionists, Romantic paintings and the art noveau style known in Germany as Jugendstil. There is also an impressive collection of sculpture from the same time period.

Among it's many paintings are works by Francisco de Goya, Paul Gauguin, Edgar Degas Woman Ironing, Edouard Manet Breakfast in the Studio, Paul Cézanne Still Life with Commode, Claude Monet The Bridge at Argenteuil (at right), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Le jeune Routy à Céleyran, Vincent van Gogh Sunflowers and Gustav Klimt Portrait of Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein.

The old Neue Pinakothek was badly damaged during World War II and had to be demolished after the war. The collection was temporary exhibited in the Haus der Kunst. The current building was opened in 1981. This museum is easy to walk through. They have a route that you can follow. Many of the rooms are lit with natural light from glass ceilings. In addition, outside they have a number of water pools with fountains and waterfalls.

The thing I liked about the art museums is that they are not that expensive. If you want to go today, the entrance fee to either museum is only five euros and they are free on Sundays.

They used to have a Vincent van Gogh self-portrait in the Neue Pinakothek. In 1938, it was confiscated by the Nazi government and labeled “degenerate art." The Nazi's did a lot of that. The Nazi's actually put on an art exhibit of what they called "degenerate art", to show how 'bad' it was. The exhibit was set up in the new Nazi art museum, Haus der Kunst (this website is only in German - they are working on the English version), built in 1937. The major purpose of the building was to display propaganda art which the Nazi's proclaimed as "truly German." The Nazi art part of the museum didn't get many visitors. However, they eventually had to close the degenerate art exhibit when thousands lined up daily to see it (the lines continued to stretch out of the building and around the corner). Needless to say, this embarrassed many a Nazi official (they sold the van Gogh). The building itself was typical of Nazi architecture. Ironically, the Nazi's are long gone, but the Haus der Kunst continues as a world-famous museum of modern art (Pinakothek der Moderne). Unfortunately, Debbie and I didn't get into this museum. They have a Henri Matisse painting Still Life with Geranium and a Pablo Picasso Madame Soler here.

We didn't get a chance to see the Glyptothek. It was commissioned by the King Ludwig I of Bavaria to house his collection of Greek and Roman sculptures (hence Glypto-, from the Greek root glyphein, to carve). It was designed by Leo von Klenze in the Neoclassical style, and built from 1816 to 1830. The Glyptothek keeps a large collection of Roman busts, among the most famous ones are the busts of the Emperors Augustus and Nero. The Second World War did not destroy much of the artwork in the Glyptothek. Unfortunately, the frescoes did not survive and only lightly plastered bricks were visible after the museum was reopened in 1972.

Near the Haus der Kunst, which is next to the Englischer Garten, is the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum (Bavarian National Museum). It is an art and history museum that mostly exhibits ivory reliefs, goldsmith works, textiles, glass painting, tapestries and shrines. This museum is only € 3 and is also free on Sunday. We didn't get in here either. We were only in München for three days!

We also missed the Deutsches Jagd und Fischereimuseum (German hunting and fishing museum) on Neuhauser Strasse. I bet you can guess why. It's € 6 and is not free on Sundays. However, it does have an interesting statue of a bronze boar in front of it.

Nazi München

On one of the days here, we took a guided walking tour of the sights of München during National Socialism called "The Infamous Third Reich Sites." This was Adolph Hitler's political party that he used to bring him to power in 1933. Its full name was the National Socialist German Workers' Party or NSDAP for short. The German word for National Socialist is "Nationalsozialistische" or Nazi for short. Hitler moved to München in the Spring of 1913, before World War I. After the war, he lived in München and became involved in the turbulent politics. In 1923, he attempted a military take-over the Bavarian government, called "The Beer Hall Putsch" which failed. Because of this, after the Nazi's came to power, the city was officially named "Hauptstadt der Bewegung" (Capital of the Movement) and the Nazi Party had it's headquarters here.

We took the U-Bahn (subway) to the Hauptbahnhof (train station) and met the tour guide. Munich central railway station, is one of the largest railway stations in Germany. It began as a provisional wooden building and was the starting point for the tracks from Munich to Augsburg. It was heavily damaged by bombings and a new building was completed in 1960. From the station we took a tram back to the Marienplatz. This was part of the route the Nazi's took during the "Beer Hall Putsch" (a "putsch" is a word for a military take-over of the government if you were wondering - kind of like a Coup de tat). On the evening of November 8, 1923, Hitler began the putsch in the Bürgerbräukeller (beer hall) where a political rally for the new Bavarian government was going on. The Bürgerbräukeller was just across the Isar River east of the town center. Hitler entered the beer hall and fired a shot into the ceiling and announced to the 3,000 thirsty beer-drinking Bavarians that a revolution had begun. Hitler had the support of World War I war hero, General Erich Ludendorff. Though successful at first, that night the plan started to fall apart. The next morning, Ludendorff convinced Hitler that the Army and Police would not fire on the General (because he was a WWI hero, of course). The Nazis could easily march into München and take it over. At 11 am, about 3,000 Nazis (most wanting a new government and some perhaps just wanting some more beer), led by Hitler, Hermann Göring and Ludendorff, begin marching into München.

After leaving the Bürgerbräukeller, they first crossed the Isar River using the Ludwig Bridge. This is the historical spot where the first toll bridge in München was built back in 1158 (a new bridge was built in 1935). There was a group of police here, but they bluffed their way through. From there, they marched up Zweibrükenstraße and through the Isartor. They marched up the Tal (past our hotel and the Altes Rathaus) to the Marienplatz. As they entered the Marienplatz, they made a right-turn onto Dienerstraße and marched north toward the Odeonplatz. This was the point that we followed the route. Dienerstraße turns into the Residenzstraße as you pass Max Joseph Platz. Here the street, next to the Residenz, gets very narrow before it opens out into the Odeonplatz. About 100 policemen were barricading the end of the street next to the Feldherrnhalle (Commander's Hall). Someone fired a shot (they are not sure who) when gunfire broke out on all sides. Hitler hit the street as 16 Nazi's and 3 policeman were killed. Ludendorff, ever the good German officer, marched up to the police barricades, where he was arrested (he was so disgusted with Hitler and the other Nazi's for not following him, he dissociated himself from them forever). Hitler was one of the first to take off leaving the others behind. He was later arrested. The putsch was over, but the Nazi Party was just beginning. Hitler went to jail for this, but 10 years later he would be elected into power. During the Nazi regime, Hitler and others would retrace the steps of the putsch through the streets of München as seen in this 1934 photo above (too bad nobody shot at them again). The site itself, next to the Feldherrnhalle, next to the Odeonplatz, became sacred to the Nazi's (it was on the wall on the left side of the building with the three arches at the edge of the picture below). They had a monument erected there with wreaths and SS honor guards. As people walked by, they were required to give the Nazi salute. You can still see the outline on the wall today where the plaque used to be.

In 1939, Hitler narrowly escaped an assassination attempt at Bürgerbräukeller when a bomb planted by a Johann Georg Elser exploded. Hitler had left a rally early and escaped the explosion that killed eight other Nazi's. Elser was arrested by the Gestapo and was murdered in Dachau Concentration Camp in April of 1945. The Bürgerbräukeller on Zweibrükenstraße survived the war, but you can't visit it today. In 1960, Zweibrükenstraße was renamed Rosenheimerstraße. In the 1970's, the Bürgerbräukeller was torn down and the Gasteig Kulturzentrum was built in its place. It's a large cultural center with a philharmonic concert hall along with a number of other cultural halls (kind of like a small version of New York's Lincoln Center).

Here is the Odeonplatz at left. On the right is the large Theatinerkirche with its massive dome. On the left is the Feldherrnhalle. The Nazi memorial would be just to the left of the building just outside the photo.

The tour left the Odeonplatz (at right), and we went to the Karolinenplatz, a few blocks west of here. It's a circular plaza named after Karolina, the mother of King Ludwig I (isn't that nice, he named the square after his mother). In the middle of the plaza is a 95 ft. high bronze obelisk commemorating the 30,000 Bavarian soldiers who, as part of Napoleon's army, died during the Russian campaign of 1812 (most of them froze to death).

From there it is a short walk to the Konigplatz (King's place). This was the center of the Nazi Party in München. They held many of their early torch lit rallies here along with their book-burning get togethers. Hitler had the whole Konigplatz paved over. At one end of the Konigplatz, Hitler had two temples built on either side of Briennerstraße. The two open-air Ehrentempeln ("Temples of Honor") contained the sarcophagi of the 16 Nazi's killed in the Beer Hall Putsch (they had eight in each). They were even guarded by SS officers. How ironic, one day these 16 were drunken beer-hall rowdies and the next day they are honored dead (This reminded me of a line that Bogart used in the movie Casablanca). The structures survived the war, but the American army had them torn down (no mention of what happened to the 16 ornate sarcophagi or their contents). You can still see the foundations today, though they are heavily overgrown with weeds and trees (in the right of the photo below) .

Next to one of the Ehrentempeln, we saw the old Führerbau on Arcisstraße (at left). This was built as an office building for Hitler himself. In September of 1938, Hitler, Mussolini and Chamberlain met in this building and signed The Munich Accords which partitioned Czechoslovakia up. The building is entirely intact, except that the two Nazi eagle and swastikas statues have been removed from the top of the facade of the building. However, you can still see where they were attached (below the blue arrows). If you want to see original black and white photos of the site go to this link.

One of the biggest ironies of the war in München was that between 1940 and 1945 there were 71 aerial bombings in München. As was mentioned above, half of München (including 90% of the old city) was destroyed. Most of its churches, museums and other historical buildings were severely damaged if not totally destroyed (along with 82,000 homes). However, most of the Nazi buildings, including the party headquarters, were barely touched.

One of the spots they take you to is a black granite memorial to the resistance movement in München (at right). The domed building in the background is the Bavarian State Chancellery (the domed part is the old Army Museum). In the summer of 1942, an anti-Nazi movement among college students sprung up in München. It was called "The White Rose" or "Die Weiß Rose." Later joined by one of their professors, they began printing and distributing anti-Nazi leaflets. They even mailed them thoughout Germany. By February of 1943, they grew more daring, painting anti-Nazi slogans on walls throughout Ludwigstraße near the University of München. A few days later on February 18, two of the leaders, Hans Scholl and his sister Sophie, dumped hundreds of leaflets into the University courtyard. Unfortunately, a University maintenance man and Nazi party member who turned them in to the Gestapo (German secret police) saw them. Other arrest soon followed. The Scholls, along with another member Christoph Probst, were tried, convicted and sentenced to death in Hitler's People's Court or Volksgerichtshof (which dealt with cases of treason against Hitler and the Nazis) on February 22 and sent to the guillotine in München's Stadelheim prison later that day (the trial, sentencing and executions lasted only four hours). Two other members, including Professor Kurt Huber, were tried and executed later in July. A sixth member was executed in October. Another member, Hans Leipelt, a former German soldier, awarded the Iron Cross for bravery in France (until he was kicked out of the army for being half-Jewish), collected money for Professor Huber's family. He was arrested for this by the Gestapo in October of 1943, along with his family, and sent to prison. In January of 1945, he was also convicted and beheaded in Stadelheim prison. Two of the members survived and live today in the United States. The Nazi judge in all of the trials, Roland Freisler, was infamous for his outbursts from the bench, screaming at and humiliating defendants. During a trial in Berlin on February 3, 1945, an Allied bombing raid hit the courthouse killing the Nazi judge.

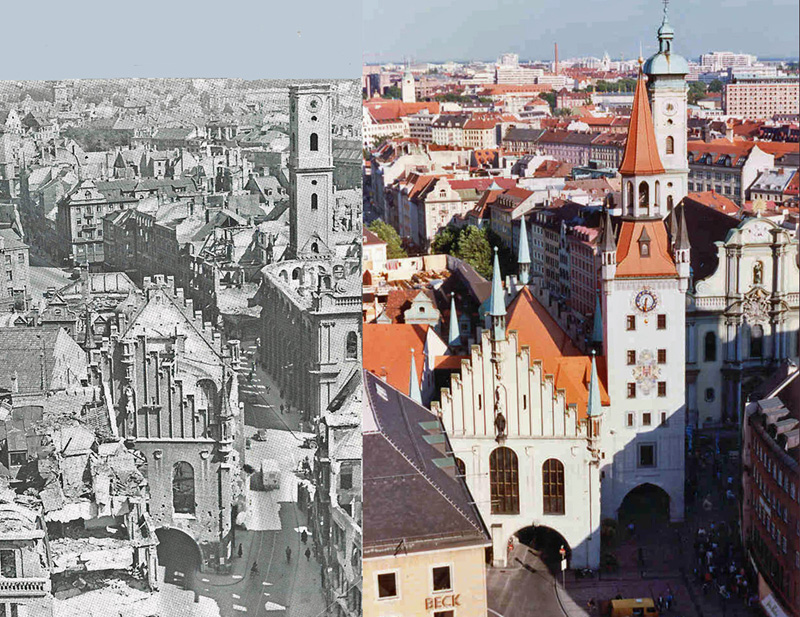

The black and white photo on the right was taken shortly after the end of World War II. The photo was taken from the Neues Rathaus next to the Marienplatz. In the right of the photo is a view of the roofless and pockmarked Altes Rathaus looking up the Tal. The roofless Heilig-Geist-Kirche is on the right of the photo. It's spire, without the copper top, is behind the church. The Talbruck gate tower is missing completely. When you look at the photo I took in 1989 at right from almost the same spot, you can see how much of München was destroyed and re-built. Some of the old buildings did survive, like the gabled and balconied building in the middle-left part of the picture on, what I believe, the south-east corner of Im Tal and Radlsteg.

The tour also goes into the fate of München's Jewish population. As is mentioned above, München had 10,000 Jewish citizens when Hitler came to power, but by the end of World War II, only 200 were alive. On the night of November 9, 1938 called Kristallnacht (or night of the broken glass), München's synagogues were torched, including the main synagogue in the Karlsplatz. Outside of München was Germany's first concentration camp, Dachau. The camp was opened in 1933 and until it was liberated by the U.S. Army in April of 1945, saw the deaths of 80,000 people, mostly Jewish citizens (of course, Dachau was small in comparison to Auschwitz in Poland which was only open for a year and a half, but saw the deaths of around two million people). Debbie and I didn't visit here during our trip (a bit depressing for a honeymoon, don't you think). However, I went there during my first trip in 1989.

Other spots of Nazi history that were not on the tour are the Sterneckerbräu across the street from our hotel on the Tal. This large building with stone archway windows and doors was once a beer hall. It was here that Hitler had his first office where he organized the new "German Worker's Party" (only had seven members at the time) including planning their first big meeting to be held on February 24, 1920 at the Hofbräuhaus. North of the train station is a four story apartment building at 27 Prinzenregentplatz. On the top floor was Hitler's first apartment in München when he moved here from Austria in 1913. Not too far away is the building at 16 Prinzenregentplatz which was Hitler's luxury apartment later on when he was the head of a powerful Nazi party. It was here that his favorite niece, Geli Raubal, committed suicide in 1931.

Eating and Drinking in München

Here we are outside the Paulaner Beer Hall in the Marienplatz. We just watched the 11am Glockenspiel show and are now sitting down to enjoy a little light refreshment. I tried the Paulaner Weißbier.