|

|

20th

Century to Present

|

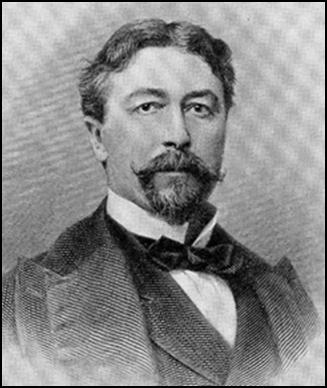

Walter

E. Edge |

||

|

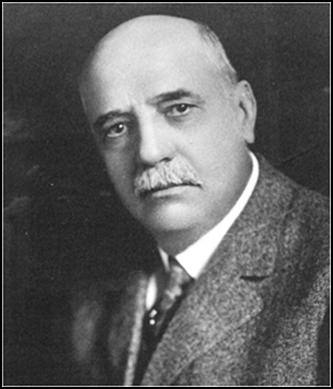

George

S. Silzer |

||

|

Foster M. Voorhees Republican

In 1894, he was elected to the New Jersey State Senate and later became the president of the Senate. During this time, he filled in as acting governor when John W. Griggs resigned to become the Attorney General of the United States. Later that year, he ran for governor against Democrat Elvin L. Crane and won. At 43, he was the youngest governor ever elected. He was also our first 20th Century governor. During his one term, he implemented reforms that benefited orphans, school systems, improved conditions for prison inmates and protected the environment. Most especially, with Theodore Roosevelt, he was the promoter of the Palisades Interstate Park along with many other environmental measures that secured the state water system and state forest service priorities. His progressive Republicanism set the stage for the reforms of Democratic Governor Woodrow Wilson a few years later. Voorhees was governor during the Spanish-American War and many New Jersey National Guard soldiers trained at Camp Voorhees before going to fight in Cuba. During his governorship, Voorhees was noted as a reform

governor – school system, corporate franchise policy, and most especially,

with Theodore Roosevelt, the promoter of the Palisades Interstate Park along

with many other environmental measures that secured the state water system

and state forest service priorities. His progressive Republicanism set the

stage for the reforms of Democratic Governor Woodrow Wilson a few years

later. After his governorship he returned to Hunterdon County where he was

born. Before his death he donated his 325 acre estate to the State, the core

of land which became Voorhees State Park. After his governorship he returned to Hunterdon County where he was born. As a philanthropist, he gave generously of his time and his estate, including leaving his 325-acre farm to become Voorhees State Park in Hunterdon County. The Voorhees Township, New Jersey is named after him. |

|

Franklin Murphy

Republican

When he returned home, Murphy went into business. Murphy & Company was nationally known as a varnish business. He married Janet Colwell in 1868. Murphy also became active in Republican politics in Newark. In the 1890's, he became very powerful politically in Northern New Jersey. In 1900, Murphy, along with current governor Foster Voorhees, was members of the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia which nominated William McKinley and Teddy Roosevelt for president and vice-president. In 1901, he ran for governor and easily defeated Democratic Newark Mayor, James M. Seymour. As governor, Murphy brought his business sense and organizational skills to Trenton. He was also very friendly toward businesses and corporations. He improved child safety laws and education. It was also a period of progressive that was sweeping the nation. Mayor Mark Fagen of Jersey City was calling for equal taxation, especially by railroads. Of course, railroad corporations were among the most powerful in the country at the time. Fagen accused the Republican Party of being controlled by the railroads. Sweeping reforms would begin under Murphy's administration. Murphy only served one term as governor. However, he remained a very powerful figure in the Republican Party. In 1908, he was considered for the vice presidential nomination (it went to James S. Sherman instead). In 1916, he unsuccessfully ran for the U.S. Senate. Despite some progressive aspects, Murphy was a conservative Republican throughout his political career. In 1912, Murphy stuck with President William Taft when Teddy Roosevelt was splitting the Republican Party. In 1920, while he was vacationing in Palm Beach, he suffered an intestinal obstruction. He died six days after an operation at age 74. There is a statue of Murphy on Elizabeth Avenue in Weequahic Park, Newark. The

13th New Jersey Regiment |

|

Edward C. Stokes Republican

Edward Casper Stokes was born in Philadelphia, the son of Edward and

Matilda Stoke. His parents who were originally from New Jersey, returned

shortly afterwards and settled in Millburn. He attended the Friends School in

Rhode Island, and graduated second in his class from Brown University in

1883. After graduation, he worked in the bank where his father worked as a

cashier.

A Republican, he entered politics and was part of the South Jersey

Republican boss William J. Sewell. With Sewell’s support, he was elected to

the New Jersey General Assembly in 1891 and served two one-year terms. He was

than elected to the New Jersey Senate in 1893 and served three terms to 1901.

As a legislature, he pushed back against gambling legislature. In 1904, Stokes was nominated by the state Republicans to be governor. In the general election, he ran against Democrat Charles C. Black. At the time, progressive movement in New Jersey that was opposed to large trust, large railroads and old time politics. Despite being a bank president and a railroad director, Stokes won the election by over 50,000 votes. He was the Governor between 1905 and 1908.

At the time, the national Republican Party was split between the “old

guard” Republicans against the progressive Republicans who were championed by

President Theodore Roosevelt. In New Jersey, the progressives were demanding

that railroads paid their fair share of taxes (railroad companies were exempt

from paying local property taxes which hurt municipalities). Stokes was a member

of the “old guard” but tried to steer a middle road between him and the

progressives. A compromise was found to increase some of the railroads tax

responsibility but it was limited.

Stokes did believe, like President Roosevelt, in nature conservation.

He got the legislature to purchase land for state forest conservation –

creating over 10,500 acres of woodland (he donated 500 acres himself.) He was

supporter of education and wanted more teachers trained to fill the

increasing public school system. He believed that immigrants, who at the time

accounted for one-fifth of the state’s population, should be taught in their

own languages and recommended increased vocational technical training for

them.

In his second attempt, Stokes won a narrow victory in the 1910

Republican primary for the U.S. Senate over former governor Franklin Murphy,

but unfortunately it was still two years before the people were allowed to

vote for senators and at the time Democrats controlled the legislature so

Stokes was defeated.

In 1913, Stokes attempted to win a second term as New Jersey Governor.

He was the Republican nominee for Governor in 1913, but lost to James F.

Fielder, who had the support of former governor and current U.S. President

Woodrow Wilson. From 1919 to 1927, he was the Chairman of the New Jersey

Republican State Committee. During that time, due to increases in the urban

population, the Republican Party’s power in the state decreased as they

continued to lose statewide elections. He felt that prohibition, under the 19th

Amendment, hurt the Republican Party. Stokes ran for the U.S. Senate in 1928 for a third and last time, but finished third in the GOP primary behind Hamilton F. Kean and Joseph Frelinghuysen. He claimed that the wealth of Kean and Frelinghuysen made a difference in the election. He opposed direct primaries for governors and U.S. senators because of the influence of money and potential for corruption. He chaired the state's GOP general election campaign that year and continued to fight against prohibition. In 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt won the election for President of the United States carrying New Jersey. Stokes felt that was because of Hoover’s support of prohibition. Despite this, with Stokes helped a number of Republicans win control of the New Jersey legislature. After this, he retired from politics. Stokes was the President of Mechanics National Bank in Trenton and was President of the New Jersey Bankers Association. Despite these positions, he never became wealthy. He lost much of his own money in the stock market crash of 1929. Learning of his financial problems in 1939, the state legislature voted to give him a $2,500-a-year pension. Stokes turned the money down and instead took a state job advising New Jersey's public information office. Stokes never married. He was an avid sports fan, especially of baseball. In 1942, Stokes died of a heart attack in Mercer Hospital in Trenton at aged 81. Because of his work with conservation, Stokes State Forest – a 16,025 acre park in Sussex County - is named in his honor. |

|

John Franklin Fort Republican

John Franklin Fort was born into a family of public officials. His father was a state assemblyman. When Fort was born, his uncle, Dr. George F. Fort was the Democratic governor of New Jersey. Fort studied law. While at law school his roommate was future 1904 Democratic presidential hopeful Alton B. Parker. Fort became a Republican and campaigned for Ulysses S. Grant for president in 1872. The following year, he passed the bar and began law practice in Newark. In 1876, Fort married Charlotte Starnsby, the daughter of the Essex County Republican leader.

|

|

Woodrow Wilson Democrat

In all,

there are 150 people buried in the cathedral. The most famous of these,

besides Wilson, are Helen Keller and her teacher Anne Sullivan, Admiral

George Dewey (Spanish-American War hero) and Cordell Hull (F.D.R.'s Secretary

of State). It was very hot that day, after the service we went to lunch in

Georgetown.

|

|

James F. Fielder Democrat

James Fairman Fielder was born in a

political family. His family descended from some of the original Dutch

settlers of The

next election would be the first time that a candidate was selected according

to the newly reconstructed primary laws. The 1913 Democratic primary had

three candidates. Along with Fielder, there was |

|

Edward I. Edwards Democrat Born:

December 1, 1863 in Jersey City, New Jersey

In 1919, World War I was over and the country was going through a turbulent period with labor strikes and Communist scares. The Republican Party was growing in power after the days of Woodrow Wilson. Republican Warren G. Harding was swept into the White House, signaling the start of "Normalcy", and Republicans won every governor’s race in the north and west of the country, that is except New Jersey. Edwards, running on an anti-prohibition campaign, which was called "The Applejack Campaign", edged out Republican Newton Bugbee with 52% of the vote. As governor, Edwards was frustrated with the Republican controlled legislature, with more rural interests, who overrode many of his vetoes. Edwards, who had urban interests at heart constantly voted against anything he thought would hurt the city workers, like public transportation fare increases and "blue laws". Edwards had successfully created an urban coalition. In 1920, Edwards was even considered as a potential Democratic nomination for president (the party went with James Cox of Ohio - who was crushed by Harding). At the end of his term, forbidden by the state constitution to run for a consecutive term, he ran for the U.S. Senate in 1922. Campaigning against the 18th Amendment (Prohibition) and with the support of the Hague Democratic Political Machine, Edwards defeated incumbent Republican Joseph S. Frelinghuysen by almost 90,000 votes. After six years in the Senate, Edwards ran for re-election against Republican Hamilton Kean in 1928. Kean came out against Prohibition also which hurt Edwards who used his "Applejack Campaign" so successfully in the past. Also, Edwards could not overcome the "Coolidge Prosperity" that was sweeping the country. He lost by over 230,000 votes. After returning to Jersey City in March of 1929, his luck turned for the worse. His wife had died in 1928 and his relationship with Mayor Hague went downhill when Hague supported A. Harry Moore instead of Edwards for governor. He went broke in the stock market crash of '29 and was implicated in a voter fraud scandal. Finally, he was diagnosed with skin cancer and ended up shooting himself in his Jersey City home at 39 Duncan Avenue. He is buried in the plot of his older brother, William David Edwards, who he once worked for, who died in 1916. |

|

A. Harry Moore Democrat

Arthur Harry Moore was born in the Lafayette section of Jersey City (240 Whiton Street), one of six children of Robert White and Martha (McComb) Moore. Moore dropped out of grammar school (Public School No. 13 – no longer there) to work. He finished his education on the side before becoming the secretary of Jersey City mayor, H. Otto Wittpenn in 1907. He married Jennie Hastings Stevens in 1911 as he continued to move up in the city Democratic circles. Two years later, Moore successfully ran for commissioner in Jersey City. When his mentor, Wittpenn, lost the governors election in 1916 and subsequently dropped out of politics, Moore teamed up with another commissioner, Frank Hague. In the Jersey City elections of 1917, Moore and Hague were re-elected as commissioners, beginning Hague's 30-year rule as mayor and the beginning of the "Hague Political Machine". While a commissioner, Moore graduated from New Jersey Law School in Newark and passed the bar. Hague, who by the 1920's was controlling New Jersey's political scene, landed Moore the Democratic nomination for governor in 1925. In the election, that featured Moore's anti-prohibition stance against the Republican's "Anti-Hague" campaign, Moore carried only three state counties. However, he won by such a wide margin in Hudson County, that he easily won the election over Arthur Whitney. Working with a Republican State House, Moore learned to compromise to get things accomplished. In his first term, he dedicated the Holland Tunnel (connecting Jersey City to New York) and Goethals Bridge and the Outerbridge Crossings connecting New Jersey with Staten Island. As the country went through the "Roaring Twenties", Moore had to deal with the social problems it caused. In 1928, the state constitution prohibited Moore from running for a consecutive term and the Republicans swept the elections for the governorship and the state house. Being in power at the time of the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression, the Republicans took the brunt of the blame. Moore waited on the sidelines for the next election. In the election of 1925, Moore criticized President Herbert Hoover and Governor Morgan F. Larson for current depression and easily carried the election over Republican David Baird Jr., winning all but one county (Baird's home county of Camden). During his second term, Moore did everything he could to cut back on spending to help the state's economic problems. Two major events, which received worldwide publicity, occurred during his second term. The first was the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932. He took personal charge of the investigation. The second was the wreck of the ocean liner Morro Castle, which burned off the coast of Asbury Park. Moore was highly involved during rescue operations. In addition, during his administration, Prohibition was repealed.

In the 1937 elections, Moore faced Essex County republican, the reverend Lester H. Clee (strangely enough, Moore's sister-in-law was married to Clee's brother). Despite the relationship, the election was very ugly. Moore’s record in the Senate (his opposition to the New Deal) was used against him. Clee carried 15 of the 21 counties, but Moore's 130,000-vote victory in Hudson County gave him the win. Clee claimed voter fraud which eventually led to a Senate investigation in 1940 (the investigation ended when it was discovered that the voting records in Hudson County had been destroyed).

Moore's third term was devoted to economic recovery as the state

struggled through the Great Depression. In early 1941, Moore left the

Governor's office for the last time. Frank Hague wanted him to run for a

fourth term in 1943, but Moore refused. He retired from public life and resumed his law practice in Jersey City where he lived at 350 Arlington Avenue (corner of Arlington and Bramhall Avenues). He served as counsel for the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad. In 1944, Moore was a delegate in the democratic National Convention that nominated Roosevelt for a fourth term. A year later, Moore was appointed by Governor Edge to the State Board of Education. While driving near his summer home in Hunterton County, Moore suffered a heart attack and died at the age of 73. The A. Harry Moore High School in Jersey City is named after him. Moore is one of only two New Jersey governors to have a high school named in their honor. The other was Harold G. Hoffman. |

|

Morgan F. Larson Republican Born:

June 15, 1882 in Perth Amboy, New Jersey

With the rise of the automobile, Larson became interested in engineering projects that would improve New Jersey's infrastructure. He worked on three major projects; The George Washington Bridge, The Outercrossing Bridge and the Goethals Bridge. The first one would connect New York City with Fort Lee, New Jersey while the later two connected New Jersey to Staten Island. Larson also passed legislation to build 1,700 miles of highways. Larson looked to winning the statehouse in 1929. Larson would first have to face Jersey City Republican Robert Carey in the Republican primaries. Ironically, Jersey City Democratic political boss Frank Hague did not want Carey to win the general election for governor, and ultimately weaken Hague's political base in the state, so he had the Democratic party machine in Hudson County support Larson in the Republican primaries to keep Carey out. Because of this, Larson won the primary. However, this backfired on Hague, who thought Larson would be easier to beat, when Larson won the gubernatorial election against Democrat Judge William L. Dill of Paterson. Larson attacked Paterson for being a Hague pawn saying he, "will enter the capital at Trenton through the front door and the Hague machine will go out the backdoor."

After the Stock Market crash of 1929, the country fell into the Great Depression. Larson did all he could to avoid the economic downturn but the growing unemployment in the state doomed the rest of his administration. Like many people, Larson believed in a Protestant work ethic and the free enterprise system, but the growing depression called those ideas into question. Many parallels were drawn between Governor Larson and President Herbert Hoover. Both were engineers who came from humble backgrounds whose administrations were undone by the Great Depression. Because of the state constitution, Larson could not run again in 1931 (you can't succeed yourself). The governor, A. Harry Moore, who he replaced in 1929, replaced him in 1932. After leaving the statehouse, Larson continued to work as an engineer for the Port Authority of New York. However, the Great Depression had seriously hurt him financially. In 1945, Governor Walter E. Edge appointed Larson to the Department of Conservation, which he held until 1949. Larson died at home at age 78 and is buried alongside his first wife Jennie. His second wife Adda was buried next to him when she passed away in 1985. |

|

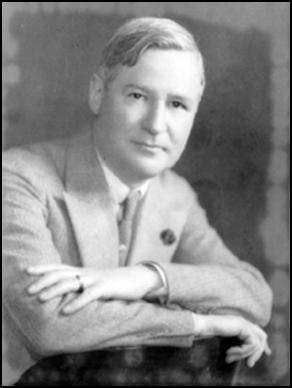

Harold G. Hoffman Republican

Hoffman will be forever linked to one of the most sensational events in the first half of the 20th century. He was governor during the Lindbergh baby kidnapping trial also known as the "Trial of the Century" (or at least the first one). After Hoffman graduated from the South Amboy High School in 1913 he worked for a few years with a newspaper. Upon the United States entry into the First World War, Hoffman enlisted into the United States Army. In France, he rose to the rank of captain in the 3rd New Jersey Infantry. After the war, he became a banker and was involved in local politics, even serving as South Amboy's mayor from 1925 to 1926. He married Lillie Moss and they had three children. A Republican, he won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives for two terms (March 4, 1927 - March 3, 1931). He chose not to run again and instead became motor vehicle commissioner of New Jersey.

Hauptmann maintained his innocence to the last and was visited in his jail cell by Governor Hoffman in December of 1935. In February of 1936, Hoffman granted Hauptmann a 30-day stay of execution which was very unpopular with everyone. It appears to some that Hoffman had serious misgivings about Hauptmann's guilt. A Board of Pardons, on which Hoffman was a member, rejected Hauptmann's appeal by a vote of 7 to 1. Hoffman was the lone vote in favor of Hauptmann. There was little else Hoffman could do, at the time, New Jersey governors did not have the power to commute a death sentence. Hauptmann was electrocuted in Trenton on April 3, 1936. The case hurt Hoffman politically. He did not want Hauptmann executed. There were calls for his impeachment, but Hoffman persisted in his claim that he only wanted to see justice done. It's not sure whether he thought Hauptmann was innocent or he felt that Hauptmann was not alone and he wanted to find out who the accomplices were. After the trial, Hoffman launched his own investigation. After his three-year term as governor, he became the Executive Director of the New Jersey Unemployment Compensation Commission until the United States entry into World War II. During the war, Hoffman again served in the army. He rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel before discharged in 1946. He returned to run the New Jersey Unemployment Compensation Commission again until his death in 1954 at the age of 58. Hoffman died of a heart attack in a hotel room in New York City. After his death, a posthumous confession by Hoffman stated that he stole $300,000 while serving in the Unemployment Compensation Commission. In 1996, the cable channel, HBO, released a movie about the Lindbergh kidnapping called Crime of the Century. In the movie, actor Michael Moriarty portrayed Governor Hoffman.

The high school in South Amboy was named Harold G. Hoffman High

School. Hoffman is one of only two New Jersey governors to have had high school

named after them (the other is A. Harry Moore High School in Jersey City). In

the late 1990's, a new high school was built in South Amboy named South Amboy

High School (the old building is still standing),

however, the South Amboy High School's mascot is still the Governor in honor

of Hoffman [Special thanks to Jon Bouchard of South Amboy for this

information]. |

|

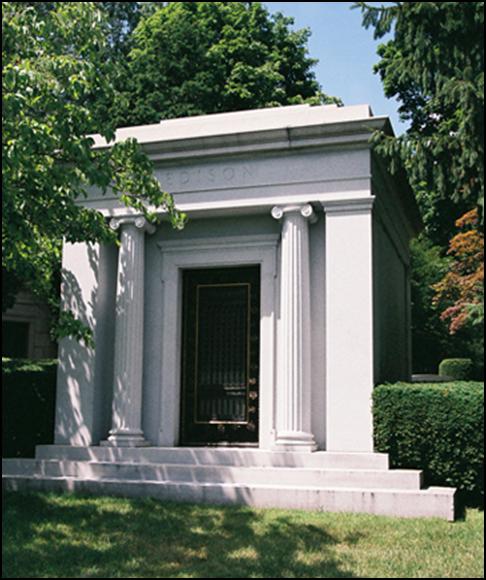

Charles Edison

Democrat

Edison is the oldest son

of famous inventor Thomas Alva Edison with his second wife Mina. He was born

at his parents' home, Glenmont, in West Orange, and later attended the

Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, Connecticut and graduated from the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts. During

World War I, he assisted his father in developing naval weapons. It was here

that he became friends with assistant secretary of the navy, Franklin D.

Roosevelt. He married his college sweetheart Carolyn Hawkins on March 27,

1918. They had no children. For a number of years Charles Edison ran Edison

Records. Charles became president of his father's company Thomas A. Edison,

Inc. in 1927, and ran it until it was sold in 1959.

During his time in the Navy department, he was responsible for

many improvements that would become critical in the upcoming Second World

War. He saw the danger posed by dive-bombers to naval ships. He pushed for

the development of fast destroyers, torpedo-bombers and torpedo boats. He

also stopped the sale of a number of obsolete World War I destroyers that

were later given to Great Britain in the early days of the war. Edison also

advocated construction of the large Iowa-class battleships, and that

one of them be built at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, which secured votes for

Roosevelt in Pennsylvania and New Jersey in the 1940 presidential election;

in return, Roosevelt had BB-62 named the USS New Jersey (today it is a

floating museum in Camden).

Edison's one term as governor was not very successful. The state legislature was controlled by Republicans which limited his ability to do what he wanted. He also quickly made an enemy of Hague, the state's most powerful Democrat, by resisting many of Hague's influences. He removed the direct phone line between the governor's office and Hague's office in Jersey City. Hague removed as many of Hague's men from state office as he could. Hague retaliated by blocking many of Edison's reforms. Edison denounced Hague with radio addresses calling him 'corrupt' and 'dictatorial.' He proposed updating the old New Jersey State Constitution of 1844 to remove many of the forms of patronage that Hague used so successfully. The constitution was also archaic in that it limited his term to three years and didn't allow anyone to secede himself, allowed an override of a veto with a simple majority and limited the power of the governor who had to share power with over 80 boards and commissions. Although it failed in a referendum and nothing was changed during his tenure, state legislators did reform the constitution in 1947. He decided not run for re-election in 1943, but was determined to be followed by an anti-Hague Democrat. However, this didn't happen as Hague was too powerful and had his man, Newark mayor Vincent J. Murphy, nominated. Edison stayed out of the election and ultimately Murphy was defeated by Republican Walter E. Edge (former 36th governor of New Jersey).

After leaving politics in 1944, Edison resumed his position as

president of Thomas A. Edison Inc. which merged with the McGraw Electric

Company in 1957 to form the McGraw-Edison Company (In 1985, McGraw-Edison was

purchased by Cooper Industries of Houston, Texas). In 1948, he established a

charitable foundation, originally called "The Brook Foundation",

now the Charles Edison Fund. He remained active in politics and supported

John V. Kenny's overthrow of the Hague Machine in 1948 (though Kenny later

proved to be as corrupt as Hague). Edison opposed the growing power of the

Executive Branch of the Federal Government, under Republican president Dwight

D. Eisenhower and Democratic president John F. Kennedy. In 1963, he

officially joined the New York Conservative Party. |

|

Alfred E. Driscoll Republican Born:

October 25, 1902 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Alfred Eastlack Driscoll, a

Presbyterian, the son of Alfred and Mattie Driscoll, was a very good student.

He graduated from Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts in 1925,

and was awarded an LL.B. degree from Harvard University in 1928. He married

Antoinette Ware Tatum and they had three children. After establishing his

legal career in Camden, New Jersey, Driscoll, a Republican, entered into

local politics. From 1938 to 1941, as a "clean government", he was

elected to the New Jersey State Senate; and in 1941 he was named the State

Alcoholic Beverage Control Commissioner. From here he established a

state-wide reputation as a watchdog of a scandal-plagued industry. He was

also a member of Governor Walter Edge's administration.

He was also instrumental in the purchase of Island State Beach Park and for improvements made to Sandy Hook State Park. He ended segregation in public schools and guaranteed the right to collective bargaining for labor unions. He gave William J. Brennan his first judicial appointment in 1949. It was a seat on the New Jersey Superior Court. In 1951, Driscoll promoted Brennan to the New Jersey Supreme Court, where he served until appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1956. When Driscoll was elected in 1946, the term was for three years. During his first term, he was behind getting the state constitution revised, changing the governor's term to a four-year term. In 1949, Driscoll was narrowly re-elected to a second term, defeating Democrat Elmer H. Wene, and would be the first to serve a four-year term. Driscoll served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention from New Jersey in 1948 and 1952. In 1952, he was considered a potential running mate for Eisenhower (the Republicans choose Richard M. Nixon instead). He was offered positions in the Eisenhower administration but turned them down to be the president of Warner-Hudnut pharmaceutical company (today its part of Pfizer Inc). After leaving office, Driscoll served as vice chairman of the

President's Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, a position he held

from 1954 to 1955. He also was president of the National Municipal League

from 1963 to 1967, as well as chairing the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and

the New Jersey Tax Policy Commission from 1969 to 1975. Driscoll died of a

heart attack in his home in Haddonfield.

Driscoll

Bridge over the Raritan River - with a total of 15 lanes, it is the widest

bridge in the world. |

|

Robert B. Meyner Democrat

After being born in Easton, Pennsylvania, Meyner's family moved to New Jersey. First living in Phillipsburg and then Paterson before returning to settle in Phillipsburg when he was 14. After graduating from Phillipsburg High School in 1926, Lafayette College (with a major in Government and Law), which is across the river in Easton, in 1930 and Columbia Law School in 1933, he began his practice in Hudson County in Union City and Jersey City. Meyner moved back to Phillipsburg three years later to run his own practice and enter politics. He was a lieutenant in the United States Navy during World War II where he saw active duty on board a merchant ship in Europe and represented enlisted men as defense counsel in court martial cases. After the war, he returned to politics. He lost a congressional race in 1946 to the infamous J. Parnell Thomas but won a state senate seat in warren County the following year by defeating Republican Wayne Dumont, Jr. He would eventually rise to be the minority leader. While in the state senate, he cast the only no vote against the creation of the New Jersey Turnpike Authority. Despite all of his work, he was defeated for re-election in 1951 by Dumont.

As governor, Meyner went against his own party leader's wishes by putting men he thought were best for the job in positions of importance. Despite Republican majorities in both houses of the legislature in his first term and a Republican Senate in his second term, Meyner succeeded in enacting his legislative proposals and building the Democratic Party in New Jersey. Meyner was known for his commitment to an open government, the promotion of rigid law enforcement, and the exposure of crime and corruption. Meyner increased state aid to education (including making Rutgers University a state university), worked to establish the "Green Acres" open space preservation system and oversaw the completion of the New Jersey Turnpike, the Garden State Parkway and the Palisades Interstate Parkway. On July 1, 1955, Meyner became the first person to cross the Paramus toll plaza, effectively opening the 165 miles of the parkway from Cape May to Paramus. Strangely enough, Meyner vetoed the legislature that put New Jersey's nickname, "The Garden State" on the state's license plates. He felt that there was no official recognition of the slogan (the veto was overridden).

Meyner became a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1960 and hoped to gain some national prominence. In the Convention, Meyner gained the spotlight by joining Lyndon B. Johnson and Stuart Symington in an attempt to block the nomination of John F. Kennedy for president. Meyner's refusal to allow his delegation to vote for Kennedy cost New Jersey the honor of being the deciding state. However, in the national election, Meyner ran Kennedy's campaign in New Jersey. After this, his political career began to go downhill. After completing his second term in 1962, Meyner returned to private law practice in Newark and Phillipsburg. Meyner won the Democratic nomination for the governorship of New Jersey again in 1969, but lost badly in the general election to Republican William T. Cahill. In 1974, his wife, Helen, was elected to the United States House of Representatives and served two terms. She was defeated for re-election in 1978. It has been said of Meyner, that as governor, he was efficient and economical. He may not have made many changes in New Jersey, but he was a good administrator. He died at the age of 81. His wife died on November 2, 1997, in Captiva Island, Florida, where she lived after the death of her husband. The Reception Center at the PNC Bank Arts Center in Holmdel was named after Governor Meyner.

There is a living legacy to him and his wife, namely, the Robert B.

and Helen S. Meyner Center for the Study of State and Local Government at

Lafayette College, his alma mater, in Easton, Pennsylvania. The

Meyner's also endowed the Robert B. and Helen S. Meyner Professorship of

Government and Public Service at Lafayette College. The

Robert B. and Helen Stevenson Meyner Papers |

|

Richard J. Hughes Democrat

Hughes' father was very active in the Burlington County Democratic Party, even serving as their chairman. After graduating from Cathedral High School in Trenton , Hughes went on to St. Joseph's College in Philadelphia. His first ambition was to be a Catholic priest, but switched to being a lawyer. After passing the bar, he opened an office in Trenton in 1932.

Hughes was named county court judge from 1948-1952. When William J. Brennen was named to the state Supreme Court, Governor Alfred E. Driscoll named Hughes as his replacement as a superior court judge, which he served until his resignation 1961. Hughes went back to private practice to support his family. His first wife Miriam had died in 1950 leaving him with four children. He re-married in 1954 to Elizabeth Murphy, a widower with three boys of her own. As Governor Meyer's second term was coming to an end, the state Democrats choose Hughes as their compromise candidate. He ran against President Dwight D. Eisenhower's former Secretary of Labor James P. Mitchell. New Jersey had never had a Catholic governor, but was assured one now since both candidates, Hughes and Mitchell were Catholic. Mitchell was better known to the people, but Hughes was a better campaigner. In the election on November 7, 1961, Hughes pulled off a major upset when he beat Mitchell by around 35,000 votes. In his first term, Hughes wanted to improve the state's operations to meet the needs of its ever increasing population. He wasn't very successful getting support for increased spending for his plans. There were even calls for his resignation. However, Hughes accomplished much during that first term including starting legislature to protect the Meadowlands from development and bringing the 1964 Democratic National Convention to New Jersey for the first time (where they went to Atlantic City).

Hughes was instrumental in getting the Port of New York Authority (today the Port Authority of New York/New Jersey) to take-over the Hudson Tubes (operated by the bankrupt Hudson & Manhattan Railroad) between New Jersey and New York City which became the PATH trains. Coupled with the take-over, Hughes, with Governor Rockefeller of New York, negotiated the plans for the building of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan.

After his plan for a state income tax failed due to a lack of bi-partisan support, he rallied the state behind his sales tax plan. His second term also saw, among many other things, the creation of the Hackensack Meadowlands Commission, the Office of the Public Defender and the start of construction of two new bridges, the Betsy Ross Bridge, across the Delaware River in South Jersey. Hughes pushed legislature that paralleled the enlarged role of the Federal government under President Lyndon Johnson's "Great Society" programs of the mid-1960's. His role in the race riots in Newark and Jersey City in 1967 and 1968 has been seen as very controversial. In 1968, Hughes headed the New Jersey delegation to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago which nominated Hubert H. Humphrey for president. Hughes was disappointed when the New Jersey went for Richard Nixon in the general election in November. He later pushed the state Democratic Party to complete reforms to make the party stronger. After he left office in 1970, he returned to private practice. In 1973, after chief justice Pierre P. Garven of Bayonne died, Governor William T. Cahill named Hughes to replace him as the Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court where he served until 1979. Hughes is the only person to have served New Jersey as both Governor and Chief Justice. 13 years later, Hughes died of congestive heart failure at age 83 in Boca Raton, Florida. His wife, Elizabeth, died of cardiac arrest in Boca Raton in 1983.

The New Jersey Department of Justice Building, which includes

the chambers and offices of the State Supreme Court, is named after him.

Hughes is the only person to have served New Jersey as both Governor and

Chief Justice. |

|

William T. Cahill Republican

In 1937 and 1938, Cahill was a special agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In 1939 he was admitted to the bar and began his political career. He married Elizabeth Myrtetus and had six daughters and two sons. His wife would pass away before him in 1991. Living in Collingswood, New Jersey, Cahill was the city prosecutor of Camden, New Jersey in 1944 and 1945, was the first assistant prosecutor of Camden County from 1948-1951 and was a special deputy attorney general of the State of New Jersey in 1951. Cahill was a member of the New Jersey General Assembly from 1951-1953. Cahill was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and served six consecutive terms until his resignation from his congressional seat to assume his seat as Governor, serving in Congress from January 3, 1959 to January 19, 1970. While there he served on the Judiciary Committee.

He lost a battle to impose a state income tax. He went directly to the voters with a proposal for the tax, which had been recommended by a commission he had appointed. However, the voters were not ready and the bill was defeated. The tax was approved four years later. On Thanksgiving Day 1971, a riot at Rahway State Prison was quelled without bloodshed. Cahill was praised for his leadership during the crisis, which occurred just two months after the bloody Attica prison uprising in New York state. Cahill was viewed as such a successful governor and formidable vote-getter (labor leaders seemed comfortable with his politics, and he did better than many Republicans among blue-collar workers) that some liberal Republicans suggested him as a running mate for President Richard M. Nixon in 1972. In the 1969 campaign, he had pledged to fight corruption and organized crime and erase New Jersey's reputation as a swampland of shabby politics. In his inaugural address, he vowed to "search out the corrupters and the corrupt, wherever they exist." Unfortunately for Cahill, they existed right under his nose. Cahill never was involved in the corruption but many of his closest political friends were. This, along with opposition to his tax proposals, would end his political career. He ran for re-election in 1973 but was challenged in the Republican primary election by then-Congressman Charles Sandman. Cahill, viewed as a moderate Republican, was defeated by the more conservative Sandman. Cahill became the first incumbent governor in New Jersey history to be denied re-nomination by his party. Sandman would lose to Democrat Brendan T. Byrne in the general election. During his final months as governor, Cahill named his predecessor, Richard J. Hughes, a Democrat, as chief justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court. After his term as

governor, Cahill was a senior fellow at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public

and International Affairs at Princeton University from 1974-1978. He died at

age 84 of peripheral vascular disease in his daughter's house in

Haddonfield. His funeral was held in Christ the King Roman Catholic

Church in Haddonfield. The William T. Cahill Center for Experiential Learning

and Career Services at Ramapo College in Mahwah was dedicated in his honor on

September 10, 1997. |

Pick Time Periods

|

This website created and maintained by Frank McGady You are visitor number: E-mail me

with any comments, questions or corrections you might have |